The man pictured, Captain William Glenny, was wounded at the Battle of Fair Oaks, Virginia, on June 1, 1862. This is his war service record, as compiled by the New York State Military Museum:

September 10, 1861. Enlisted at Ithaca, NY, as a Captain

October 25, 1861. Commissioned into Company E, 64th New York Infantry

June 1, 1862. Wounded at the Battle of Fair Oaks, VA

May 5, 1864. Promoted to Major

November 30, 1864. Promoted to Colonel

March 13, 1865. Promoted to Brigadier-General

July 14, 1865. Mustered out at Washington, D.C.

Glenny was born on May 31, 1831, in Virgil, New York, to William Glenny and Ruth Chaplain. He lived for several years in Kansas, before returning to New York State to marry Helen M. Barnes, the daughter of Reverend Herota P. and Susannah Barnes. In 1860, the couple lived with Helen's parents in Ithaca, while Glenny was working as a merchant of a dry goods store. William and Helen's first daughter, Alice, was born in 1854, and their second, Mary (nicknamed Minnie), in 1861.

|

| 1860 US Federal Census |

|

| Ithaca Daily News August 18, 1911 |

My transcription:

Camp of the 64th Regt. NYVNothing in this letter really stood out to me until the end. Glenny discusses the need for a commander of the regiment who is actually present, the weather, and the understandable desire of his men to see their service end. Then there is that last paragraph: "Mrs. Glenny is with me in camp, 'bound to be a soldier.'" Helen Barnes Glenny had accompanied her husband to war!

Near Germania Ford

Virginia January 30th 1864

H. A. Dowe

General

Your favor of 23rd [illegible] came duly to hand.

Since writing you nothing new touching the case under consideration has transpired. The petitions forwarded to the two gentlemen in question have not yet been heard from.

Accompanying I send you a certified copy of a petition signed by every officer present in the regiment. Our brigade is so reduced in numbers of its officers that the major of this regiment is in command. Since this brigade was formed it has been under command of a colonel who is now absent with his regiment in Pennsylvania they having reenlisted. One colonel is absent with leave the other is commanding the division.

If our brigade commander was present it could readily get his indorsement [sic].

Our field officer may not regard the petition we forwarded them if not the matter will be delayed until we can send it where it will and when the time comes if the case requires immediate attention I will endeavor to telegraph you (and unless directly to the contrary) in what ever words it may be couched you may understand it means go to Albany.

We have been having a spell of as fine weather as I ever saw in the month of May and during mid day have sought the shade of my tent for pleasure and comfort. Our army is in a state of quiet but much scattered owing to having a long line of front to guard.

There is occasional skirmishing by our advanced pickets a few days since the Rebs had a litlte brush among them selves. Said to have been caused by some of their number trying to desert.

From recent orders I should not be surprised if the army was considerably reorganized before active opperations [sic].

General Hancock is making an effort to recruit this corps to fifty thousand men for special service.

Men in camp are great for rumors, and they have one now to the effect that the three years men whose time expires within the present year are to be discharged the first of April. It probably grew out of the fact that a bill to that effect is before Congress. I have not seen it.

It might not be politic but would be no more than justice to the few left who have borne the heat and burden of the day and received no bounties.

As newspapers give all items of interest touching news of the day and from the army I will not trespass upon your time further than to say Mrs. Glenny is with me in camp, "bound to be a soldier."

With regards I am very respectfully your obt servt and friend

Captain William Glenny

This one sentence raises so many questions. What role did Helen play in the camp? Did Captain Glenny encourage her to join him or did she insist on it? Did she bring their two daughters with her? Was Glenny's remark "bound to be a soldier" written in jest or was it an accurate reflection of Helen's attitude? Was she there to fight or simply to be with her husband?

|

| Women, children, and soldiers in a Union Army camp (source) |

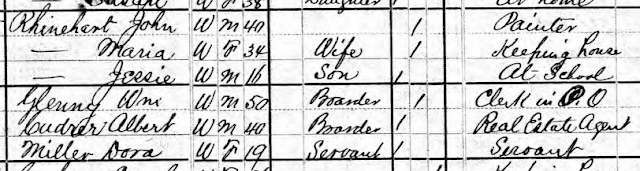

After the war, William and Helen returned to their home in Ithaca and Helens' parents, and William resumed his dry goods business in Ithaca. He was later appointed Ithaca postmaster by President Ulysses S. Grant.

|

| 1870 US Federal Census |

|

| 1880 US Federal Census |

|

| 1880 US Federal Census |

|

| New York Herald September 30, 1883 |

|

| Randolph Weekly Courant January 12, 1888 |

|

| New York Herald July 3, 1890 |

|

| (Source) |

|

| General William Glenny (source) |

On January 28, 1900, a memorial service for Glenny was held at the First Methodist Episcopal Church in Ithaca, with addresses given by Reverend W. H. York and Colonel T. B. White. According to the Ithaca Daily News, the church's auditorium "was filled to overflowing by members of the congregation, comrades of the Sydney Post, G.A.R., the Sons of Veterans and the Woman's Relief Corps." The article goes on to describe the elaborate decoration of the church and the hymns sung, and lastly prints the addresses given by York and White.

To be quite honest, these addresses left me a bit disappointed. They contain few hints as to what Glenny was actually like, aside from the fact that he was a "manly man" who lived up to nineteenth-century ideals of masculinity. And of course in many ways he must have, but a person is more than a type. I doubt that either York or White knew Glenny personally. Below, I've quoted some of the less platitude-laden parts of their addresses.

Reverend York:

"General Glenny, as you will learn from another, who knew him and knew his history well, was a brave soldier in camp and on the battle field. He was an upright and good man as a servant of his country in the capacity of a citizen. Those who have lived nearest him bear a precious testimony to his courage and bravery in the sick room because of his faith in God ..."Colonel White:

"He lives in the memory of those who knew him in his religious life as a man inoffensive in conduct and a man charitably disposed to others; a man with a great heart sympathy for suffering humanity; but a man who could stand firm as a rock when he encountered sin and iniquity; a man of prayer, and a man of faith in God."

"I am not here to recite to this people, who have known General Glenny ... the story of his life. It has been an open book, known and read by his neighbors and his townsmen, and their verdict is, 'He was a manly man.' Filling public stations of responsibility and trust honorably, in private life blameless, his manhood exhibited itself in his obedience to the call of his country ... In twenty battles he led his company and regiment, and they who followed him accord to him the honor of being a manly man and officer in all the difficult details of his military career."This was Glenny's obituary in the New York Times, January 8, 1900:

|

| New York Times January 8, 1900 |

|

| Ithaca Daily News November 27, 1915 |

|

| Cornell University, Summer 2010 |

Cowell died in 1923. His and Mary's daughter Natalie married William Sumner Smith, a shoestore manager, in 1916. They raised their three children - William, Natalie, and Nancy - in Chicago, Illinois. William worked in a shoe store and later as an insurance agent. Natalie Cowell Smith died in 1977.

William and Natalie's son William Sumner Smith Jr., who was born in 1918, died on December 18, 2012, at the age of 94, and is survived by his wife Josephine, four children, nine grandchildren, and eight great-grandchildren. William and Natalie's daughter Natalie died in 1993; their daughter Nancy is still living.

- William Glenny m. Ruth Chaplain

- William Glenny (1831-1900) m. Helen M. Barnes (1832-1915)

- Alice L. Glenny (1854-1876)

- Mary E. Glenny (1861-) m. Alexander Tyng Cowell (1859-1923)

- Natalie R. Cowell (1885-1977) m. William Sumner Smith (1880-)

- William Sumner Smith (1918-2012)

- Natalie Elizabeth Smith (1922-1993)

- Nancy Smith (b. 1925)

No comments:

Post a Comment