The following article from the New York

World, published September 8, 1893, was sent to me via Facebook by Mike Savoca, a descendant of one of the

Spencer Optical factory workers.

General Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832-1904) was the first director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Born near Turin, Italy, he fought for the British in the Crimean War, then immigrated to the United States and served in the American Civil War. His estate in Mount Kisco, which abutted that of the notorious

Judge Leonard, was sold to him by Albert and Mary Sarles in the 1880s.

General di Cesnola's reputation is somewhat tarnished by his haphazard methods as an amateur archaeologist and by allegations made by art dealer Gaston Feuardent that the general made deceptive restorations to the Cypriot artifacts in his collection (which formed the Cesnola Collection of the MMA). Feuardent's allegations, mentioned in the article below, were generally true. However, the focus of the article is another controversy: that surrounding di Cesnola's treatment of an old graveyard on his property that supposedly contained the remains of Patriot soldiers, in addition to members of the Kirby and Hewlett families. The "troubles" between the villagers and di Cesnola seem to echo those between the villagers and Judge Leonard. In each case, the villagers reacted with shock and disgust to the selfish abandon with which a wealthy man abused his power. On the other hand, both di Cesnola and Leonard felt they had the right to do with their property as they pleased.

The question is now, does anything remain of the graveyard that di Cesnola destroyed? I am currently on the case. Thanks to Mike for sharing this with us.

Patriots' Bones Dug Up.

Mount Kisco People Say Harsh Things About Gen. di Cesnola's Act.

AN OLD BURYING-GROUND EXCAVATED FOR A DWELLING.

Commissioner Daly Ordered Cesnola's Overseer's House Removed, and the General Moved It Into Burying Ground - Gen. Cesnola Says Only Two Bones Were Dug Up - He Says It's His Burying-Ground, Anyway.

Gen. di Cesnola, of Cyprus and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, has been rummaging among dead men's graves again. It has been known for years that the General was the owner of a private graveyard. Not that he made it himself, the way they do in Texas, but he bought it outright.

It was in 1882 that Gen. di Cesnola bought the graveyard. He bought it as part of a tract of seventy-five acres of land about a mile and a half east of Mount Kisco. He bought it of Albert Sarles, and Sarles had bought it of Hulett. Hulett had bought it of the Kirbys, who owned over a thousand acres of land in and around New Castle Corners, an outlying flank of the village of Mount Kisco.

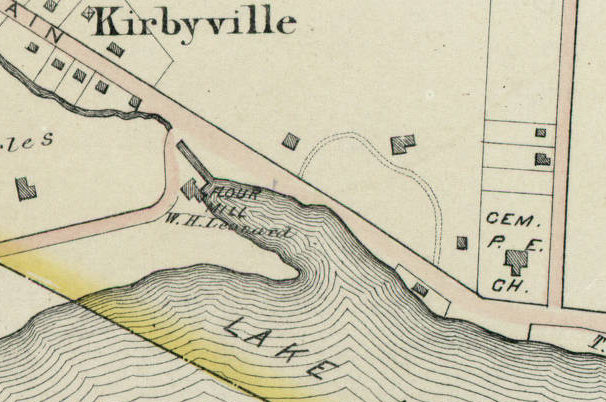

The tract of land which Gen. di Cesnola bought bordered the eastern and northwestern side of a long, irregular little sheet of water known for generations back as Kirby's Pond. Judge Leonard bought the pond two years ago, blew up the dam which made it a pond, drained it, and made some very soggy meadow land on which bullfrogs and bullrushes thrive.

Down at the southerly end of this pond there jutted out into it a little wooded peninsula which for over two hundred years has been used as a burying-ground. It began as a private burying ground for the Kirbys. Then when the Huletts came into possession they buried their dead in it. It was thrown open by courtesy to other families in the neighborhood, so that for a while, strictly speaking, private property, it came to be in reality a public place for interring the dead. Many soldiers of the Revolution killed in the fighting above White Plains were buried there.

The General had hardly time to acquaint himself with all the features of the land he ha bought before a committee of three waited upon him. They were substantial American citizens and sound Presbyterians and came to see the General about a rumor. The rumor was that the General, being a Catholic, was bound to do just what the Catholic priest had told him to do and the report was that the priest had told him to rip up that Protestant burying-ground and scatter the bones and dust of the dead to the four winds of heaven.

The General relieved their minds. He told them that he was not going to disturb the burying-ground. He told them furthermore that when he submitted to the dictation of any Catholic priest, Cardinal or Pope, as to what he should do with his own private property, he would be a very much older and very much c hanged man from what he then was.

That was trouble number one.

Then a man named Feuardent broke loose. Feuardent was a sceptic and a scoffer about the Cyprian treasures which the General sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for such a tidy sum of money. Feuardent said that Di Cesnola was a fraud. Di Cesnola replied.

In the heat of the debate Feuardent accused di Cesnola of having just bought another graveyard in Westchester County for the purpose of ransacking it for skulls and coffin plates to sell to art museum gulls.

That was trouble No. 2 about the graveyard, and now we come to the third and last of the General's burying-ground woes.

That began about six weeks ago, and it originated in the office of Michael T. Daly, Commissioner of Public Works. Commissioner Daly, in his efforts to keep the source of the Croton water supply from contamination, promulgated an edict that the house in which William Garrison lived had to be moved. Garrison had been overseer of Gen. di Cesnola's farm for over ten years. He said if the house was moved he would have to throw up his job and move, too, for he could get no place near by to live in.

Gen. di Cesnola was perplexed, but he had an inspiration. Why not put Garrison in the graveyard? As he thought of it it grew in his estimation to the proportions of a great scheme. He carried it out. He hired Pete Archer to move the house Garrison had lived in bodily over to the graveyard, and before he did that he hired William Wetherell to scoop away enough grave-tops and dig down into enough grave-bottoms for the house to rest on and have a cellar under it.

It was this despoiling of the last resting place of the dead, and particularly of the patriot dead of the Revolution, which has brought down upon the General the final and most serious of all the verbal attacks which his purchase of the graveyard has developed. It is discussed with much bitterness by people for miles around Mt. Kisco and Newcastle Corners.

The General had not been popular with the country people to begin with, and this last act has made them like him less than ever. Extravagant stories as to the number of the bones dug up and the sacrilegious way in which they were handled are going about. As a matter of fact but few bones were dug up. Just how many is a matter of dispute. William Archer says he only saw two and that they were leg bones. This is what Gen. di Cesnola says:

"The house is not in the graveyard proper, but in the front of it. I was present during all the excavations and present for the very purpose of seeing if any bones and relics were turned up. I am too much interested in antiquities to let an opportunity like that pass. If any bones were dug up I intended to put them in a coffin and have them decently interred. Two bones were dug up. They were leg bones, but whether of a man or a woman I could not tell. I told my overseer to put them aside and take care of them. He did put them aside, but the next morning they were gone, and since then we have not been able to find any trace of them. That is all there is to the story.

"The place was never a public cemetery, and if people choose to sell the land in which the bones of their forefathers rest they must not complain if strangers show as little respect for the place as they have shown. The proprietorship of that land lay between me and Judge Leonard. Judge Leonard said if I did not claim it he would. My deed fully shows that it was included in my purchase, and in a suit I had with a telegraph company that was putting up lines Judge Dykman, at White Plains, held that it was mine. Nobody has said anything to me about what I have done, but I suppose they talk among themselves."

Gen. di Cesnola scraped away the soil for the foundation and a little back yard to the house for a depth of about three feet. About [illegible] feet distant from the line of excavation there are two tombstones in good condition, one of white marble and the other of brownstone. Both are moss grown, but the inscriptions are very plain. One reads:

In

Memory of

Rosannah

Hewlett

who died

July 2, 1836

Aged 67 years

3 months and

Four days

The other, which is the one of brownstone, erected to a member of one of the Kirby family, and this is all that bear legible inscriptions, although there are the outlines of scores of graves visible, many of which have only the broken stubs of headstones sticking out of the ground and are evidently very ancient.